Davis’s only formal instruction in art was limited to the drawing classes he took in high school. From 1939 to 1968, he worked as a sportswriter, journalist and White House correspondent in Washington D.C., Jacksonville, and New York. He frequently visited museums and galleries in New York and Washington, especially the Phillips Collection where he became familiar with Paul Klee and Pierre Bonnard.

When he began to paint in 1949, Davis realized his nonacademic background freed him from the limitations of the traditional academic approach to art. Although his early works on canvas and paper showed the influence of artists such as Paul Klee and Arshile Gorky, his work developed a very distinct, spontaneous character.

In 1950 Davis became involved in the Washington art scene. This is how he met artist and curator Jacob Kainen, who introduced him to the Washington Workshop Center for the Arts and the artists working there among whom were Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland. Davis’ first solo exhibition of drawings was held at the Dupont Theater Gallery in 1952. He presented his first exhibition of paintings at Catholic University in 1953.

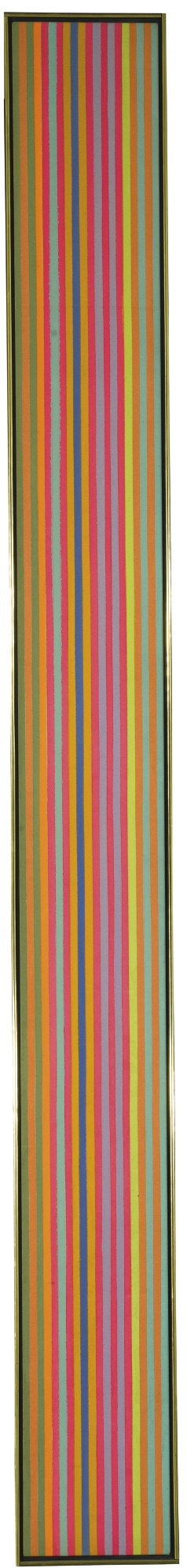

Davis became a member of the first generation of Washington Color School painters, along with Howard Mehring and Thomas Downing. In 1952 Davis developed his signature vertical stripe composition, beginning with Black Flowers (1952).

At the end of the 50s, Davis’ developed his mature style that was characterized by vertical stripes in discrete hues placed in an edge-to-edge arrangement. Davis was strongly influenced in creating his technique by Kenneth Noland and Morris Louis, who were closely connected to the New York art scene particularly through the influential critic, Clement Greenberg. They shared with Davis the excitement and experimental nature of New York’s art scene. In particular all three practiced a new technique of staining and soaking unprimed canvas with acrylic, which Davis used in Red Devil (1959).

In his stripe paintings Davis continued the spontaneity that characterized his early works. His choice of colors was not based on any theories or formulas but rather followed a sort of visual improvisation.

In 1965 Davis’ work was included in Washington Color Painters, a traveling show held at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art that officially launched the Washington Color School as a visual arts movement. In 1966, he began teaching art at the Corcoran School of Art and Design. He later taught at American University, Skidmore College, and the University of Virginia.

Davis contributed to the establishment of Washington D.C. as a contemporary art scene, and played a significant role in the development of the color abstraction movement that achieved prominence in the 60s. He has been identified as the leader of the Washington Color School. Although his work was generally considered within this context, his paintings from the 60s, characterized by hard-edge, equal-width stripes, were very different from those by Louis or Noland. In discussing his work, he spoke not only about the importance of color, but also about “color interval,” a rhythmic, almost musical effect caused by the irregular appearance of color shades within a single composition.

Through the 70s he began creating large scale installations, including Franklin’s Footpath, a large striped composition he painted on a street in front of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, and Niagara (measuring 43,680 square feet), painted on a parking lot in Lewiston, New York. In 1974, Davis was awarded the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation Fellowship. In 1984, he was appointed commissioner of the National Museum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, in Washington D.C.

Davis is predominantly remembered for his abstract colored stripe works, but it is important to acknowledge the fact that he was a versatile artist who worked in different formats and mediums. In addition to painting, he produced prints, video and neon abstract pieces.